Abstract. Culture is rooted more deeply than analogy, symbolism, experience, or any conscious impulse. The archetypal structuralist model of an axial grid of typology, raises individual and social subconscious behaviour to conscious appreciation; and challenges the paradigm of cumulative conscious constructs. The core content of culture is a set of specific recurrent features, hard-wired into nature and subconscious behaviour; measurable and predictive in artworks, built sites and alphabets worldwide; and testable against about 100 details of an inter-dependent structure of five layers. The archetypal model includes twelve to sixteen character types (each with specific optional features, at specific average frequencies); their sequence; an axial grid between the eyes or focal points of specific pairs of opposites; five central area limb-joints or junctures; and the seasonal time-frame of the artist’s culture. Structuralist anthropology is a viable science, despite its recent detour into animism and perspectivism. Structuralism offers social perspective and therapy to the current age of global migration, population, socio-economic and environmental shock, perceived as ‘culture’ shock.

KEYWORDS: archetype, art, axial grid, built sites, expression, structuralist anthropology, subconscious.

By Edmond Furter. Independent structuralist anthropologist, author of Mindprint (2014) and of Stoneprint (2016). Edmondfurter@gmail.com

- Introduction

Anthropologists and their informants seemed to share the paradigm of culture as a cumulative, conscious system or construct. Terence Turner (2009) cited ‘ethnographic evidence for significant, fundamental features of conceptual construction, and meaning of specific categories and propositions, that differentiate Amazonian societies [from one another], and from Modernist ideas.” In this paradigm, no idealist model could account for variations among cultural systems. But some myths indicate an archetypal paradigm, and several media express universal structure. Primordial animals and ancestors hold prototype objects, “self-existing, self-objectifying things and behaviours, found, appropriated, never made. People copied these.” (Turner 2009). Post-structuralism sought a midway to escape the impasse of nature v culture dualism: “Humans produce, or regulate in culturally standardized ways, internal bodily processes of transformation, that give rise to aspects of social personhood. Such products, either artefacts or conceptual knowledge, cannot be simple, internally homogeneous classes, or in a semiotic order of signification, or ethno-scientific taxonomy; but complex schemas of heterogeneous elements and levels of features, comprising transformational steps in a process of mediating relatively natural to cultural forms.” (Turner 2009). The present study demonstrates the complex schema (Furter 2014), but it is clearly innate and natural. The central question of What is human, now finds and answer in structuralist anthropology: We replicate natural structure and meaning, but appropriate it as ‘products’ of our faculties.

1.2. Structuralist failures

Structuralist anthropology had failed to demonstrate specific invariable principles, processes or patterns in cultural behaviour or artefacts; beyond ritualisation of obvious natural structures such as kinship. The field had found only apparently arbitrary details in myths, cosmologies and other crafts; and failed to isolate any comprehensive abstract structure. The ideal of formulating behaviour, as in economics, linguistics, semiotics and psychology, may seem to reduce culture to innate perception of natural categories and meaning; yet formulas grant access to subconscious social processes; reveal our place in nature, and thus answer the central question of human sciences, as Turner (2009) noted. But Claude Levi-Strauss was “the last major anthropologist to focus on that question”. Turner noted fundamental flaws in raising any cultural duality, such as nature v culture, to the level of a paradigm; and applying a rigorous model to apparently ‘fluid’ data. But several ‘splinters’ in cultural functions remained ‘beams’ in scientific paradigms. Viveiros de Castro (1998) had identified “implicit philosophy in interpretation” as requiring a ‘bomb’ to breach. Animists and Perspectivists magnified the dualist flaw into multi-culturalism, reducing nature to culture, thus repeating the Aristotelian error of allowing logic to override observation. Human sciences struggled to find the ghost in behaviour, despite the success of structuralism in natural sciences.

1.2.1 Society disrupted science

Anthropology is “an effort to understand human nature through systematic study of qualities in us, that vary in time and place, and those that don’t…” noted Peter Wood (2015). But Wood immediately recognised the dominant evolutionary and diffusionist paradigm; “…and how we emerged as a species, diversified into thousands of languages, tribes, and civilizations.” Despite “steadfast determination to stand outside the myths people tell themselves, to see things as they really are,” social anthropology had “learned the trick of promoting new myths in the name of de-mythologizing.” This failure of anthropology applied to all human sciences; inability to rise above socio-political agendas, such as rationalisations of colonialism, egalitarianism, social guilt, nostalgia, ideologies, and vague institutional agendas such as ‘curation’ and ‘education’. All the conscious and subconscious uses and abuses of culture remain scientific baggage. Anthropology remained partly untested popular philosophy, an extension of cultural crafts, as in divinity or art history training.

Structuralism, also named Ecological or Symbolic, was also distracted by social anthropology applications, labelled Political Economy, Ideology, or Cultural Construction of self v other; including some simplistic data, pragmatic interpretations and populism (Endicott et al 2005). Science had never studied cultural crafts sufficiently to inform practitioners or users at a paradigmatic level, despite the example of the successes of popular psychology. Culture consumes anthropology on its own terms; as critique of Modern Western thought and society, or as the supposed voice of ‘pure, primitive’ cultures.

1.3 Structuralist successes

Structuralist anthropology did influence human sciences and technologies, but under other labels, such as animism. A minor structuralist revival in the 2000s applied behavioural algorithms to data collection and interpretation, prompted by computer automation. One journal editor had declined a draft of this paper because the author was “the only structuralist anthropologist left”. But Turner (2009) had demonstrated transformed structuralism in supposedly post-structuralist and deconstructionist models. Levi-Strauss’ (1955) “Mathematics of man” had added impetus to cybernetics, information technology, machine interface, and artificial intelligence (AI), now one of the main fields of science and technology. His search for the machine in the ghost of culture was partly product of, and partly a prod to automation. Reconstructions of geared layers of the Antikythera device from a BC shipwreck, and Chinese clock towers, are reminders that our innate impulse to automate nature into logic, is timeless. George Boole (1854) had abstracted some behaviours into mathematical formulae using binary quantities, 1 and 0, as functions of And, Or, or Not. His book, Laws of thought, inspired programmers a century later. Structuralism may resemble a time-bomb, but it is alive in all sciences and crafts. Godel in Vienna, competing with Russel in England, found that logic applied to sets; could be consistent or complete; but not both. This paper describes five layers of structure, each consistent with itself (isolated from 700 examples), each with sets of optional features. In WWII, Alan Turing came across an Italian engineer’s description of a lecture on the failed Difference Engine of mathematician Charles Babbage, interpolated by Babbage’s student, Ada Lovelave, estranged daughter of Lord Byron. Ada was inspired by the Spinning Jenny and Jacquard’s punch-card looms, to propose extending automation beyond numbers. Babbage soon designed the Analytical Engine, but lost parliamentary funding. Turing mechanised letter code permutations in an electro-mechanical Universal Machine, nicknamed ‘The Bomb’ for Allied intelligence at Bletchley Park, to crack German Enigma codes. His colleagues built the Colossus machine on Boolean logic, to crack German Loren codes. A year after WWII, a science fiction magazine story imagined a world-wide web. Turing had noted in his book in 1950 that it was impossible to predict which problems a computer could solve; and that some logical solutions would remain improvable. He also predicted artificial intelligence, provided that rules of behaviour could be isolated. This idea was controversial, and is likely to remain so even after the discovery of subconscious behaviour (Furter 2014, 2016). Bletchley Park work was classified until the 1970s, but soon influenced some civil applications. Binary code, Nasa’s moon missions, magnetic tape, Xerox windows, Steve Wozniac’s Apple, and circuit miniaturisation all required user-friendly interfaces. Hard sciences technologised natural structure despite lacking theories, or ‘Shut up and calculate’ in the post-war tech axiom. The web was realised sixty years after the war, when Vint Cerf’s integration of defence and civil security agency radio and electronic networks escaped via academia into the corporate world in about 2000. Within a decade it was the largest and potentially most integrative and democratic artefact ever made.

Big budget science and tech banks on unravelling natural structure, as in the Large Hadron Collider, and in serving innate behaviour with animist applications such as ‘social media’. Structuralist anthropology seemed political, un-falsifiable, and incapable of breaking cultural or natural codes, but practitioners had misunderstood and abandoned it.

1.3.1 Synthesis requires structure

Turner (2009) proposed that natural-cultural structure resided in transformations, such as maturity cycles. Ironically, this development itself signified a phase in scientific maturity. Physical sciences co-operate to infer invisible structures in nature, such as bio-chemistry and physics; enabling applications in social crafts, such as health care and environmental management. Human sciences have access to massive data from the cultural record, including Google algorithms, but lag behind in theory, interpretation and applications, despite several efforts at synthesis, as by Talcott Parsons (Hays 1958). The humanities shy away from studying some core content of cultural behaviour, such as spiritual crafts, in any universal or comprehensive context. Education and training serve cultural crafts mainly by perpetuating media praxis, such as art, divinity and literature; in local, temporal, and political contexts. The net result of specialisation and occupational praxis is a post-modernist lack of context, and an unexamined general scientific paradigm.

Cultural qualities tend to relate to categories of natural, social and economic values (as Max Weber had recognised); such as species, elements, organs, functions and tools. Even apparently simplistic features such as ‘bag, weapon, or mixing’, have inherent meanings and abstractions that enable ‘grammar’ in perception, thus inviting structuralist study of perception, within consciousness levels, human nature, physical nature, and ultimately principles of matter and energy. Thus culture may offer as much access to immutable laws, or archetype as a self-calibrating standard, unaffected by place and time; as nature does. Jung and Jaffe (1965) had noted: “Again and again I encounter the mistaken notion that an archetype is determined [by cultural influences or experience] in regard to its content… It is necessary to point out once more that archetypes are… determined only as regards their form, and then only to a very limited degree.” This study indicates that even ‘forms’ (such as major gods, in Jung’s example), are global, thus natural, and not ‘culturally determined’ either. Even average numbers of selections of optional character features are global (see frequencies in Table I and the graphs).

Some archetypal themes are conventionalised (such as the creative vortex or churn, in the Hindu and rock art examples below; or healing trance rituals in San, Siberian, and other polities). Typology now emerges as the once elusive recurrent “motifs in the jet-stream of time.” (De Santillana 1969). Demonstrations of recurrent behaviour (see Data sources below) now confirm that we have individual and collective compulsions to re-express the innate canon, algorithm, blueprint, or ‘grammar’ in all our media; as affirmation and therapy in the broadest sense of the term. Demonstration of inherent commonalities, and superficial differences, offers conscious context to subconscious behaviour that may be valuable in the era of dynamic global migration and supposed ‘culture’ shock. We are now more diverse than even the Sumerian, Indus, Persian, Hellenic, Roman or Colonial empires.

The archetypal model challenges paradigmatic assumptions about supposedly ‘liberal’ arts and culture as artefacts of ‘development’. The subconscious expression model is highly testable. Universality of language and architecture validates testing of features of grammar or architecture; but invalidates the nurture model. Innate language capacity does require some transfusion, thus language is a multi-generational artefact. Likewise, transfusion could not sustain any cultural media without innate, natural, structuralist features in perception, ecological context, and in meaning itself (Furter 2017a). Any application of generic culture imposes its own layer of arbitrary elements or styling, for polity bonding, appropriation and exploitation. The thin layer of arbitrary features may likewise be subject to rigorous rules, a subject for further study. The present study offers a model to isolate, study, predict and automate the blueprint of subconscious and social behaviour.

1.3.2 Structuralist formulae and paradigms

James B Harrod (2018) demonstrates that an algebraic group-theory formula of Andre Weil was the format for Levi-Strauss’ kinship model, also applied to some aspects of ritual, artistic design, built site layout, and agriculture field layout. Levi-Strauss had formulated aspects of myth into aggregates, to extract various Functions (Fx, Fy), acting on Terms (a, b), relative to ( : ) other, swopped or substituted Functions and Terms; thus Fx(a):Fy(b) ~ Fx(b):Fa–1(y). ‘Deep structure’ as used by Levi-Strauss and Chomsky fell out of academic fashion, but the formula was revived and automated to reveal recurrent motifs in cultural and scientific texts. Harrod had earlier (1975) revised the Weil-Levi-Strauss formula to quantify myth as an unfolding process, instead of a structuralist analogy. Instead of Straussian opposites such as ‘a v a–1’ in an equation of ratios, Harrod proposed a set of transformations (>), demonstrated in qualities of self-awareness, in ‘animist’ mode. His Revised Canonical Formula (rCF) uses equations that are “asymmetric, non-linear, non-reversible, inverse by transformation”. He proposes “networks of semantic complementary binary opposites in cultural-value space”. He found “no universal application in the evolution and history of culture forms”, and concludes that culture and cognition ‘evolves in stages’, after the individual maturity model of conscious cognition. Yet he explained “creative imagination” as “not derived logically, [but] constrained or channelled by the formula.” The difference between ‘constraint’ and archetype could be a flimsy semantic veil, obscuring the large and testable semiotic structure in nature and culture (Furter 2017a).

- Blueprint in cultural media

The present study confirms that pairs of spatial opposites play some roles in archetypal expression, but challenges Harrod’s conclusions by expanding evidence of global application of a more concrete, less abstract, and more layered formula, with limited content.

2.1 Data sources

Data for Table I and the graphs, are from 265 artefacts, including 170 artworks and rock art works (Furter 2014); 45 built sites (Furter 2016); and 50 seals, including 25 ancient and 25 classical seals (Furter 2018c); all from a wide range of cultures and eras. A further 500 artworks (400 listed in Furter 2014) and 55 built sites confirm the five inter-dependent layers of structure. It is near impossible to find any artwork, built site, or cultural set with eleven or more characters, that does not express the standard structure, or doubled adjacent structure in cultural works with about 22 to 38 characters. Even semi-geometric shapes are kinds of characters (Furter 2015b).

2.1.1 The archetypal structuralist model

The five subconscious layers of expression are: (a) typological characters with specific optional features; (b) peripheral sequence, clockwise or anti-clockwise; (c) axial grid between eyes or focal points of pairs of opposites; (d) three pairs of polar junctures, implying three planes; (e) orientation of one polar pair vertical or horizontal to the ground-line or a cardinal direction, often indicating the seasonal time-frame of the artist’s culture.

Types could be labelled after any popular set. Generic labels, such as social functions used here, avoid the false impression of diffusion from any particular medium or culture. Zodiac seasons and decanal hour myth labels were used initially, requiring repeated clarification that they do not arise from conscious invention or diffusion. Correspondence theories are often misled by archetypal recurrent features, or by citation of parallel expressions among media and cultures; into assuming diffusion, and ignoring innate nature.

Numbering of the transitional c-types change in this paper, from 3c 6c 10c 14c in previous publications, to 2c 5c 9c 13c, for easier use of alphanumeric Sort functions in data. Their positions remain the same.

Recurrent behaviour subconsciously and rigorously follows several quirky rules. Type characters always have their eyes (except a womb at 11, and a heart at 12/13; or interior focal points in built sites), on the axial grid formed by pairs. Spatial elements in culture resemble cosmology, but both express archetype, and do not derive from one another. Cultural artefacts express two ‘galactic’ poles (4p, 11p); two galactic crossings (7g, 15g); an annual or Ecliptic Pole at the axial centre; and two ‘celestial’ poles (Cp and Csp) or midsummer and midwinter. Poles are not expressed by eyes, but limb joints (junctures in built sites). Four types could be double, as in Figure 1 (1v8 and 2v9; 5a v12 and 5b v13), or single (only 2v9 and 5v13); thus the total is usually sixteen or twelve. Some other pairs are doubled in complex artworks or built sites.

A shift in the position of two or three eyes could erase the sequence and the structure, but almost never does so. Axial grids are not inherent in any collection of about eleven to twenty items. Morley’s miracle (1899) applies only to the equilateral shape of an inner triangle, formed by the intersections of lines that trisect the corners of any irregular triangle into three equal parts. In axial grids, angles are irregularly unequal. Napoleon’s theorem applies only to some predictable properties of equilateral triangles, based on the edges of a triangle. Axial grids are not based on lines of equal length.

Table I. The minimal twelve type characters in any artwork, built site or craft set.

Label; known archetypal features with known global average frequencies:

1 /2 Builder; twist 44%, cluster 23%, bovid 19%, bird 19%, tower 18%, build 14%, sack 10%, hero 10%, book 8%, rain,

2c Basket; weave 25%, container20% instrument 20%, shoulder-hump 20%, hat 15%, snake 10%, throne 10%,

3 Queen; neck-bend 31%, dragon 19%, sacrifice 17%, queen 13%, school 12%, spring 10%, fish 6%, ovid 5%,

4 King; squat 30%, rectangle 28%, king 22%, twins 13%, sun 12%, bird 10%, fish 8%, furnace 8%, field 5%,

5a/5b Priest; varicoloured 37%, priest 34%, hyperactive 33%, tailcoat-head 32%, assembly 30%, horizontal 28%, water 24%, heart 24%, large 24%, bovid 20%, winged 14%, invert 12%, reptile 10%, sash 8%, equid, ascend,

5c Basket-Tail; weave 16%, tail 14%, U-shape 10%, contain 8%, herb 4%, oracle, spirit (ka), spheres,

6 Exile; in/out 58%, horned 44%, sacrifice 30%, small 14%, U-shape 13%, double-head 12%, caprid 8%,

7 Child; rope 24%, juvenile 24%, bag 22%, unfold 13%, beheaded 10%, chariot 8%, mace 6%, off-grid,

7g Galactic-Centre; limb- joint 38%; juncture 34% (throne, altar, spiral, tree, staff); path/gate 18%; water 16%,

8/9 Healer; bent 28%, strong 28%, pillar 28%, heal 22%, disc 14%, metal 8%, ritual 6%, canid 4%,

9c Basket-Lid; disc/hat/lid 27%, instrument 25%, reveal 16%, hump 15%, weave 8%,

10 Teacher; W-shape 44%, staff 36%, hunt master 24%, guard 20%, metal 14%, market 14%, disc 12%, council 11%, snake 8%, ecology 8%, school 6%, wheel 5%,

11 Womb; womb 88%, wheat 15%, water 14%, tomb 11%, interior 8%, library 8%, law 5%, felid 5%,

12/13 Heart; heart 83%, felid 42%, death 34%, rounded 21%, invert 14%, weapon 11%, war 9%, water-work 8%,

13c Basket-Head; oracle 14%, head 14%, weave 8%, ship,

14 Mixer; in/out 43%, time 28%, tree 20%, angel 15%, bird 11%, antelope 10%, dancer 8%, felid 8%, reptile 4%, carapace (eg caryfish, turtle), ungulate (eg donkey), mix or energy flow (somewhat ambiguous with certain other types, and arguable, and of low frequency),

15 Maker; churn 44%, rope 28%, order 27%, rampant 26%, bag 20%, mace 16%, doubled 16%, face 12%, canid 12%, sceptre 11%, smite 8%, reptile 8%, winged 8%,

15g Galactic Gate; junct 30% (river 10%); limb-joint 12%.

Polar features (see the triangles in the centre of Figure 1) also follow universal average frequencies. The axial centre is usually unmarked at about 60%, or on a limb-joint or juncture, expressing both ends of a polar axle, and thus the projection angle.

4p Gal.S.Pole; mark 82%; limb-joint 67%; juncture 17% (spout 12%, stream, speech),

11p Gal. Pole; mark 88%; limb joint 64% (hand 12%, elbow 10%, foot 12%, etc); juncture 24% (door 12%, corner, etc),

Midsummer (cp); Limb-joint 54%, or juncture 24%.

Midwinter (csp); Limb-joint 46%, or juncture 24%.

One of the polar axles is on the horizontal plane 50%, or vertical plane 12% (or on a meridian or latitude on a built site). Polar markers usually place midsummer on or near type 12, 13, 14 or 15 (see Figure 1), implying spring and the cultural time-frame 90 degrees earlier (in seasonal terms), as Age Taurus1, Taurus2, Aries3 or Pisces4. Some recent works are framed in Age Aquarius5a, which started in 2016 (Furter 2014). The type hosting spring, 1, 2, 3 or 4, is often prominent. The general theme of a work is indicated by features shared among three or more characters. Works express about 60% of the optional, measurable, recurrent features.

Categories of the identified features are apparently inconsistent with conscious logic, indicating subconscious access to archetypal logic. Rigorous average frequencies, and consistency through millennia, also rule out learning, nurture or conscious revisions. The full repertoire appears in the oldest examples, about BC 26 000 (Furter 2014), ruling out accumulation of idiosyncratic ‘ideas’, and of localised cultural ‘frameworks’, as some cognitive archaeologists suggest for San art of the last millennium (Lewis-Williams and Pierce 2012).

2.2 Structuralist labelling

| 1Builder | 2Builder | 2cBasket | 3Queen | 4King | 4p |

| 8Healer | 9Healer | 9cLid | 10Teacher | 11Womb | 11p |

| 5aPriest | 5bPriest | 5cTail | 6Exile | 7Child | 7g |

| 12Heart | 13Heart | 13cHead | 14Mixer | 15Maker | 15g |

| cp | csp | ? | ? | ? |

Table II. Labels for marking typological features in cultural artefacts.

Labels are used in pairs of spatial opposites, here given above-below one another. Some pairs may remain unused; often the transitional c-types, or two of the four doubled types (1v8, 5a v12) may remain unexpressed in a work. Characters with eyes off the grid, without a limb-joint on a polar point are labelled ?. Numbering follows the horary (hours) sequence, also used in divination and emblems such as the Tarot trumps (Furter 2014), validated against atomic (proton) numbers in the periodic table (Furter 2016). Pairs of opposites are seven or eight numbers apart: 1v8, 2v9, 3v10, 4v11, 5a v12, 5b v13, 6v14, 7v15. Magnitudes are fifteen or sixteen numbers apart: 1:16, 2:17, 2c:17c, 3:18, 4:19, 5a:20, 5b:21, up to about 64, expressing base15 and base16, confirmed by chemical groups, and transition elements analogous to the four c-types. Proposed type numbers are probably archetypal.

2.2.1 Frequency graphs

The line graph could be traced in axial format (see the version of this paper on Researchgate.net), with direct spatial analogy to how artists use canvases, and how communities use built sites.

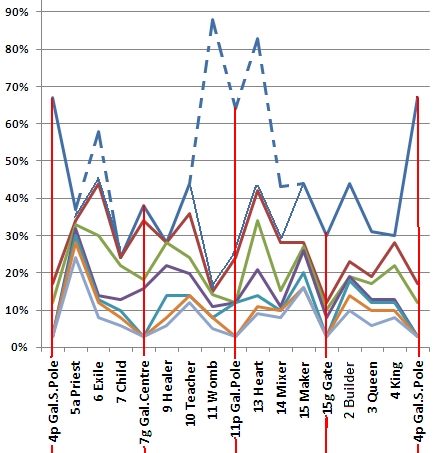

Adjacent combined or split types 1 /2, 5a/5b, 8/9 and 12/13, express the same features at nearly the same frequencies, thus they are combined in data, causing minor peaks in the graphs. These four may be differentiated into eight types in future. Frequencies peak around type 11p, with a secondary peak around type 4p opposite. Four of the highest frequency features have spatial elements (here marked by dotted lines), in addition to their sequence position: type 11 has her axis on her womb; type 12/13 has his axis on his heart; types 6 and 14 are notably ingressed to, or egressed from the centre of the artwork. Frequency ranks indicate some interplay between the typological or ‘ecliptic’ plane, and the frequency or ‘galactic’ plane. The time-frame or ‘celestial’ plane seems to affect only seasonal features.

3. Structured art ‘design’

Table III. Typological characters in a Vishnu pillar drawing (noting archetypal features):

1 Builder; Ring instrument of Vishnu (twisted).

2 Builder; Vishnu (twisted), some features of flanking types (NO EYE).

2c Basket; Umbrella (lid), and flower (cluster), and king’s rattle (instrument). C-types are off the grid, in their sectors.

3 Queen; King with four heads (necks, dragon, spring).

4 King; King (king).

5 Priest; Priestess (ritual).

5c Basket-Tail; Snake tail (tail).

6 Exile; Turtle (reptile), at the centre (extreme ingress).

7 Child; Pony, multi-headed (unfolding, decapitated), with saddle (bag).

8 Healer; Puller (strong?) without rope.

9 Healer; Pot? (NO EYE).

9c Basket-Lid; Three pots, closed (lid).

10 Teacher; Lotus goddess (arms up, autumn, balance).

11 Womb; Dog midriff (womb).

13 Heart; Elephant chest (heart).

13c Basket-Head; Ship (ship, container, texture).

14 Mixer; Elephant person with snake heads (mix, energy), far out (egress).

15 Maker; Two (double) dogs (canine) on churn snake (rope). Some functions are at 1 /2.

15g Galactic Gate; Vishnu lower hand (limb-joint).

The axial centre is on the turtle head (perhaps neck in the original artwork; limb-joint?).

11p Galactic Pole; Bow (juncture).

Midsummer (cp); Turtle front upper claw (limb-joint), or on the churn base (juncture).

Midwinter (csp); King’s foot, or knee (limb-joint). These markers imply spring and the cultural time-frame as either Age Taurus2-Aries3 (about BC 1800), probably the perceived era of cultural formation; or Age Pisces4, contemporary with the work. The central top character as a spring marker indicates cosmological Age Taurus2, however most alchemical works express that time-frame.

The main general theme here is type 15 Maker, of ropes, churn, re-creation and canines. This theme appears worldwide. Another general theme in the work is type 10 Teacher; arms-up, staffs, balance.

De Santillana et al (1969) popularised ethnographic archaeo-astronomy in Hamlet’s mill, reading Icelandic and several corresponding cosmic motifs as diffused and degraded ‘astronomy’. They indicated the possibility of innate subconscious impulses, but argued for diffusion. Archaeo-astronomy still reads myth as coded astronomy or proto-science, and does not investigate the role of archetype, and thus nature, in culture, nor in scientific practice.

4 Structured rock art ‘design’

Nanke cave in Zimbabwe was part of a set of oracles, on par with Bronze Age and classical Greek, Egyptian and other sites. Roman spiritual centres such as the oracle of the dead at Baia, in the volcanic Bay of Naples near Rome, also had paintings at their entrances; likewise destroyed to re-distribute spiritual authority (Paget 1967. Temple 2003).

Table IV. Type characters in a Nanke Cave painting (noting archetypal features):

1 Builder; Shoulder-head of rope-man churn (twisted), leaning on staffs (trance, of 8 opposite).

2 Builder; Rope-man churn (twisted) (NO EYE).

2c Basket; Shoulder-head rear, ropes (weave). C-types are usually off the grid.

3 Queen; Ostrich (long neck).

4 King; Antelope cow?, with young.

5a Priest; Antelope running (active).

5b Priest; Bowman spanning (active).

5b Priest B; Priest? (ritual?), axis on his chest (heart, of 13 opposite) and three with beams (horizontal).

6 Exile; Antelope (horned). And swimmer (ingress).

7 Child; Swimmer or walker.

7g Galactic Centre; Swimmer, arms up (limb-joints?), staff (of 10). Some apparently interrupted artworks indicate that visual expression spirals out as bags or limbs (named ‘formlings’ in archaeology) from this junction.

8 Healer; Swimmer in churn centre (strong?), at rope-man’s legs (pillars).

9 Healer; Swimmer? (NO EYE).

9c Basket-Lid; Fish pool churn wave (weave, lid).

10 Teacher; Swimmer (arms up?).

11 Womb; Pregnant womb (womb).

12 Heart; Runner?

13 Heart; Lion (felid), axis on chest (heart, confirmed by 15-14-13 flat outline).

14 Mixer; Dancer (dance), arms up, staff (of 10).

15 Maker; Antelope between two ropes (rope).

15g Galactic Gate; Antelope rump (limb joint).

The axial centre is unmarked as usual.

4p Galactic S. Pole; Small bowman’s feet? (limb-joint?).

11p Galactic Pole; Bender’s shoulder (limb-joint).

Midsummer (cp); Churn’s front elbow (limb joint), on axis 14-15, implying spring and the cultural time-frame as Age Aries-Pisces, probably the perceived era of cultural formation. But midwinter (csp) could be on the churn’s hip (limb joint), on the axis 5, implying spring and the cultural time-frame as Age Taurus, typical of alchemical works in all cultures, and supported by the centrality and prominence of types 1 and 2. Structuralist time-frames are approximate.

The main general themes here are type 15 Maker and 15g, ropes, churn, re-creation, and limb joints. This theme also appears in Indian art and myth, as a milky ocean of soma at the former spring equinox. The infinity wimple also expresses totality of responses to external pressures, named ‘panarchical discourse’ in history (Gunderson et al 2009); or ‘phase transit’ in chaos theory 3D graphs. Another general theme in the work is type 10 Teacher; arms-up, staff, hunt master, ecology.

5 Structured campus at Delphi

Table V. Typological characters at Delphi Apollo (noting archetypal features):

1 Builder; Krateros column (tower).

1 Builder B; Apollo temple west chamber.

2 Builder; Stadium stairs. Statue of Auriga, Charioteer.

3 Queen; Apollo temple centre, slain dragon (dragon, long neck, sacrifice). Stage apron Hercules frieze of tamed monsters (dragon, sacrifice).

3 Queen B; Archaic building.

2c Basket; Apollo’s interior omphalos stone (monster head) in a net (weave), sunken (2 pool). Statues of Krateros saving Alexander (2 twisted) in lion hunt (3 bent neck).

4 King; Dionysus two identical buildings (twins), brother (twins) of Apollo (king), twin (twins) of Artemis. Apollo Dolphin (fish) inner door, in building of two east-west diagonals (twins).

5a Priest; Apollo’s hut of bay branches, wax, feathers, bronze (varicoloured), two eagles (elemental, cardinal). Apollo as Zeus (priest), eagles crossed (4p juncture) to drop omphalos. Knydian hall (assembly), mural of wooden horse (equid).

5b Priest; Apollo Sitalcas, Grain Guard (of 10), highest at 70ft (large); Daochus, draped (sash), leg flexed (4), a Delphic priest (priest). Entrance pillar of Prusias2 of Bithynia, equestrian (equid). Euremedon palm (6 tree) by Agamemnon’s charioteer (equid). Many features (varied).

5c Basket-Tail; Neoptolemus sanctuary; Syracusian treasury; tripods (oracle) of Gelon and Hiero; Aemilius Paulus pillar for PrusiasII of Bithynia, equestrian (equid); Acanthus plant column (6 tree), three graces under a tripod (oracle. 6 chair) holding a cauldron (container); Sockle stone.

6 Exile; Attalos portico, protruding (egress); Chios altar (sacrifice); Akanthian treasury.

7 Child; Rhodian chariot (chariot); Plataian tri-serpent spiral column (unfolding. 8 snake); under a golden tripod (6 chair).

7g Galactic Centre; Athenian porch. Central gate (gate) to Kastalian spring (water).

8 Healer; Prytanaion, fire altar (flame).

9 Healer; Cyrenean; Corinthian; Athenian stoa (pillars).

9c Basket-Lid; Corcyrian Bull revealed (oracle) a tuna school (ophiotaurus, snake-bull, transition).

10 Teacher; Market gate (market). Statues of Aegospotiamoi; Arcadians; and Philopomen. Spartan Admirals (guard) monument, Lysander crowned (crown).

10 Teacher B; Statues of Spartans, Athenes, Argives, wolf logo (canid); Threshing floor, Halos (11 crops), where Apollo kills a fountain dragon (3 opposite).

11 Womb; Argive King’s crescent (interior). Seven Epigonoi crescent (interior). Both of Argos, ‘Wheat Field’ (crops).

12 Heart; Sikyonian treasury interior (interior), reliefs of war (war), spears (weapons). Cnydian treasury, Triopas, Artemis shooting (weapon) at Tityus.

13 Heart; Siphnian treasury interior (interior), frieze with lions (felid), gods in battle (war) v giants. Cnidian interior (interior).

13c Basket-Head; Sibylline rock (oracle).

14 Mixer; Theban, protruding (egress). Boeotian. Athenian, central (ingress).

15 Maker; Bouleuterion, ‘bread, chew, talk’ (order), of local council (sceptre).

15g Gate; Sanctuary of Ge (15 creation). Asklepius. Two main SW gates, Gymnasium gate (gates).

The axial centre is probably unmarked, as usual.

4p Gal. S. Pole; Dionysus stairs (juncture). Kassotis spring (spout). Site’s long axis (juncture). Alyattes’ silver wine bowl on spiralling iron bands (junctures). Apollo (4 king) pronaos cauldrons.

11p Galactic Pole; Threshing floor (11 crops) south corner (juncture), site’s long axis (juncture). Tarantines’ captive women (11 wombs). The galactic polar axle is on the site’s long axis (juncture).

Midsummer (cp); Had moved from the Sibyl rock north edge, near the north-south cardinal, to the tall Naxian winged sphinx column (junctures).

Midwinter (csp); Had moved from the Apollo temple left corner, to the platform left corner (junctures). These markers placed the site’s subconscious ‘summer’ in 14 and 15, thus ‘spring’ and the cultural time-frame as Age Aries and Age Pisces (from about BC 1500, and from about BC 80); both ahead of the Age of the builders. ‘Predictive’ time-frames are typical of national legacy sites (Nemrut, Turkey, in Furter 2016: 238-241). Oracle sites seem to emphasise express the four transitional types (2c, 5c, 9c, 13c).

Delphic Apollo sanctuary nestles in a larger scale stoneprint in the area (not illustrated here; see note under 5b), wherein it probably expresses type 5 (assembly, varicoloured, ritual, hyperactive); as the Vatican City stoneprint is geared to the Rome stoneprint; as some Izapa stele engraving mindprints (such as the tree of life engraving) are part of a stele cluster stoneprint, which is part of a pyramid cluster stoneprint, which is part of a pyramid field stoneprint; as Teti’s pyramid group nestles in the Sakkara pyramid field stoneprint; as the Gobekli Tepe engravings form part of the houses, which express a larger scale stoneprint on Gobekli hill (Furter 2016, and 2016b; Expression 15).

Practical and conscious motivations are independent of subconscious archetypal structure. For example, Greek buildings were oriented by surveying one diagonal (crosswise, corner to corner) on a cardinal direction (east or north). Ranieri (2014) listed diagonal orientations of 200 Greek temples, including sixteen buildings of the Delphic Apollo sanctuary. The only overlap between regular geometry or celestial orientation, and the subconscious stoneprint, is in one element of the time-frame orientation. In Delphi, the galactic polar axle co-incides with the long axis of the site.

6. Structured city in Brussels

Table VI. Typological characters in Medieval Brussels (noting archetypal features):

1 Builder; Congress Square obelisk (tower); and The Unknown Soldier; and Barricades Square.

2 Builder; Graphic Story centre (2c texture).

2c Basket; Paribas Fortis Bank (moving to a new building at type 13c in 2018).

3 Queen; Martyrs Square (sacrifice).

4 King; Our Lady (womb, of 11 opposite) of End of Earth, outside early medieval Brussels, and of Good Success. Northward lies the Atomium and Mini Europe.

5a Priest; Opera (hyperactive).

5b Priest; Origin Court; and Mint; and John Baptist of Beginnings, of camel skin coat (tailcoat). Outside the wall is another John Baptist.

5b Priest B; St Catherine, flying angel on a pillar (hyperactive, horizontal); Charcoal Lane, Brick lane (varicoloured); near St Géry and Notre Dame aux Riches.

5c Basket-Tail; Stock Exchange; St Nicholas, black (varicoloured), of merchants (varicoloured).

6 Exile; St Gorick. West lies the cruciform Realm building.

7 Child; Our Lady of Good Assistance, of nurses with bags (bag). A miraculous statue was found on Compostella pilgrimage route (bag). Former St James hospital. Large Market (bag, rope).

7g Galactic Centre; Fountain Square (water, light). Synagogue. St Anthony near the wall (juncture).

8 Healer; Peeing Boy fountain, Juliaanske ‘extinguished a bomb fuse to save the city under siege’ (strength feat), formerly of stone (pillar).

8B Healer; Near Europe statue (pillar). Axial centre of Brussels gates (strength. Not illustrated). Parliament (OFF GRID).

9 Healer; Our Lady of the Chapel, relics of St Boniface of Brussels opposed (strength) corrupt king FrederickII, and Francois Anneessens, beheaded for civil rights (strength).

9c Basket-Lid; Courts of Justice (10 enforcement, balance), ‘Gallows’ Hill.

10 Teacher; Our Lady on the Table, south facade.

11 Womb; Our Lady (womb) on the Table (platform, interior). A healing statue from Antwerp to the Crossbow guild.

12 Heart; St Jacques of Coudenberg; was chapel of Charles Quint. Royal Square (bastion). Palace 1500s, hall of Burgundy Dukes (bastion) ruin, 1775 Revolution law court (war), 1802 church.

13 Heart; Royal Palace (weapon) interior (heart).

13 Heart B; Brussels Park south pond (water-work).

13c Basket-Head; Brussels Park north pond. New Paribas Fortis Bank (bastion) with inner garden (interior), moved from 3 in 2018.

14 Mixer; National Palace. Former park (tree).

15 Maker; Cathedral Sts Michael and Gudule (doubled), Belgian patrons. Archbishop of Mechlin-Brussels (doubled), royal church (sceptre), ducal graves (sceptre). An 1100s church site. Window of LouisII of Hungary and his queen kneeling before Trinity (churn).

15g Gate; Freedom Square (juncture).

The axial centre is south of St Hubert Galleries, on the Montagne-Sculptor Roads intersection (junction).

11p Galactic Pole; Mont des Arts Park (juncture).

Midsummer (cp); Cathedral Square south end (juncture). Midwinter (csp); St Hubert Galleries south facade, on the east-west cardinal (orientation). These markers would place summer in 14-15, thus spring and the cultural time-frame as Age Aries-Pisces, at the start of the Christian era. The north-south cardinal indicates cosmological Age Pisces, contemporary with the work. Gates in the defensive wall of Brussels from another stoneprint around the old city centre, as in Piacenza, Rome, and elsewhere (see note on gates, at 8 above). Structuralist analysis of Brussels compares well with Paris (Furter 2017b) and London (Furter 2018b).

7. Structured emblems and alphabets

Some calendars, emblems and alphabets have similar sounds, numerals (in alphanumeric sets), pictographs, determinants, and related myths; in sequences that could be directly compared to one another, and to typological features isolated in artworks and other media, indicating that the natural blueprint extends to all cultural media. Some sets have fewer characters, usually skipping one of the doubled types (see __ blanks in Tables VII B and VII C). Alphabets have often been compared to hour asterisms to trace supposed diffusion, but never in the context of archetype informing various media (see Babylonian Plough Stars decans in Furter 2018a).

Cretan Archanes seals could be sequenced by archetypal features. The sets are highly stylised, and apparently without secure traditional sequence or fixed total. Comparison to other Cretan media, via the mindprint model, could resolve the sequence. About 26 often reproduced features include abstract ‘determinants’ that may be subconscious former or current spring markers (see types 2, 3, 4). These may compensate for lack of spatial layout and polar features. The set may illustrate a calendar or some other cycle, yet both sets would reveal collective and individual subconscious inspiration in the culture, in the re-designer, and in copyists.

Table VII. Typology in some Cretan Archanes seals.

Type; Upper Image (features); Lower Image (features):

2 Builder; Shelter or Trap (maze); on Antelope (bovid).

3 Queen; Flower (spring); on Horse (neck), Snake (dragon).

4 King; Two S-shapes (twins); on Horse (equid).

5a Priest; Zebra or horse (equid? colour?).

6 Exile; U-shape (U-shape).

7 Child; Centaur? In ropes (rope).

7g Gal.Centre; Hills or abstracts (unfolding?)

9 Healer; Podium (pillar), Herb (heal), Bent (bent).

10 Teacher; Double-axe (staff) of Apollo (teacher), Snake (snake, heal), Staff (staff).

11 Womb; Staff or Wheat (crops), Plough? (furrow?); Vase (womb).

11p Gal.Pole; Flower (junction).

13 Heart; Purse or Hand or Heart (heart?).

14 Mixer; Honey? (energy?), Brewer? (transformation).

15 Maker; Leg (smite? rampant?).

7.1 Structured Germanic runes

The conventional 18 runes have graphic and phonologic counterparts in the Latin alphabet. The six others making up the conventional set of 24 runes, derive from a North Italic alphabet in the first century AD (Looijenga 1997). However runes assumed their own sequence, and set of emblematic derivations, both now testable against archetypal typology. Runes are conventionally listed from F, Wealth (here type 1 B). The tables follow Latin convention from A 1 (type 14).

Table VII B. Typology in Semitic alphanumeric sets (after Goldwasser 2006), v 22 Germanic runes, v Hour decans (after Furter 2014).

Type; Sound Numeral; Rune (features); Hour decan

14 Mixer; A 1; Speech (jaw, limb-joint); Ursa Minor.

15 Maker; B 2; Bough, Family (sceptre, ancestor); Canis Min.

15g Gate; G 3; Gift (bag); Galactic Gate or Canis.

1 Builder; D 4; Sun (former spring); _____.

1 Builder B; F/V 5; Wealth (bovid); Hyades.

2 Builder; W/Ng 6; Hail (rain, cluster); Pleiades.

2c Basket; Z/Gw 7; ____; (Diphthong)(transit); Algol.

3 Queen; EH 8; Horse (neck); Pegasus.

4 King; TH? 9; Thorn, Hammer (spring); Pisces Cord.

4p Gal.S.P.; Y/R? 10; Tree (junction); Pegasus neck.

5a Priest; K 20; Flame (4 furnace); Aquarius latter.

5b Priest; L 30; Water (water); Aquarius prior.

6 Exile; M 40; Man (scapegoat?); Cygnus?

7 Child; N 50; Chariot (chariot); Sagittarius.

7g Gal.Centre; Xi 60; Constraint (junction); Serpens Cauda.

8 Healer; AY Y 70; Home (hearth, heal); Scorpius Sting.

9 Healer; P 80; Hearth (hearth, heal); Scorpius Antares.

10 Teacher; R? 100; Ride (9 trance); Bootes.

11 Womb; HD 90; Fork, Tyr (10 staff, arms), Star Spica.

12 Heart; S 200; Ship (interior); Argo.

13 Heart; T 300; Horn, Bull, Sun (ruler); Leo Regulus.

14 Mixer; U 400; Joy (honey?); Beehive?

15 Maker; PH 500; Couple (double), Spell (churn); Gemini.

7.2 Structured Mayan day hieroglyphs

The Mayan ‘month’ of 20 days, part of the Tzolk’in, 20×13=260 days, has its own set of emblematic ‘derivations’, now testable against archetypal typology. The 20-day birthday cycle is a powerful predictor of personality globally, independent of annual seasonal calibrators and of Western astrology. Mayan days are conventionally listed from Crocodile or Water (here type 3). The tables follow Latin convention from A 1 (type 14).

Table VII C. Typology in Semitic alphabets (after Goldwasser 2006); v 20 Mayan day hieroglyphs, Limbs, and Images (after Pinzon 1995); v Hour decans (after Furter 2014).

Type; Sound Numeral; Mayan hieroglyph (features); Limb, Image; Hour decan.

14 Mixer; A 1; Vulture (bird); Tongue, Spirals (polar); Ursa (polar).

15 Maker; B 2; Motion (churn, polar); ____; Ursa Minor (polar).

15g Gate; G 3; Knife (risk); mouth (joint), Skull?; Orion Club (junct).

1 Builder; D 4; Rain (storm); Eye, ____; Orion.

2 Builder; F/V 5; [Sun?]; ___; ___ [Mayan skip]; Hyades?

2c Basket; W/GN 6/7; Flower (cluster); Eye, _; Pleiades.

3 Queen; EH/Th 8; Croc (dragon); Chest, _; Cetus Tail.

4 King; TH? 9; Wind (field?); Lung (furnace), _; Pegasus.

4p Gal.S.P.; Y R? 10; House (junct, pillar); _; Pegasus legs.

5a Priest; K 20; Lizard (reptile); Hip?, ___; Aquarius.

5c B.Tail; L 30; Snake-knot (reptile, weave); Genital, R/snake; Capr.tail.

6 Exile; M 40; Frog (fish), Death (sacrif); Ear (bleat), _; Capr (fish, goat).

7 Child; N 50; Deer (juvenile?); Ear, ______; Sagittarius.

7 Child B; Xi 60; Rabbit (juvenile); Foot (joint), _; Tail, Serp.Cau., Tail.

7g G.Cntr; AY 70; Water (junction); _, _; Galaxy (water).

8 Healer; P 80; __; __; __ [Mayan skip]; Scorpius Sting.

9 Healer; R? 100; Dog (canid); Foot, ____; Lupus.

9c Lid; HD 90; _____? (diphtong)(transit); __; Serpens.

10 Teacher; S 200; Monkey (arms); arms (arms), Lizard (arms); Bootes.

11 Virgo; T 300; Grass (crops); womb (womb); _; Spica.

11p Gal.P.; U 400; Reeds (junct); _______; Coma (hair).

12 Heart; PH 500; Ocelot (‘felid’); Foot, __; Leo retro.

13 Heart; CH 600; Eagle (bird, polar); Hand; __; Ursa.

8. Conclusion

Hundreds of examples confirm that the large, specific, layered, rigorous repertoire of global, subconscious, individual and collective behaviour, is measurable and testable in several cultural media. The archetypal structuralist model of direct, simplistic features, made complex by their inter-dependence, indicates that archetype eternally guides and bounds re-expressions in nature and culture. This model challenges the paradigm of culture as ‘conscious’, with ‘creative options’ that ‘evolve’; and challenges correspondence theories and diffusion theories in science and in popular culture. The largely unstated and untested general paradigm is common to human sciences, and thus likely to resist data, models and even evidence to the contrary (Thomas Kuhn 1966). Evolution is one of the archetypes eternally dominating human sciences, by analogy to individual and technological maturity curves; which actually depend on ecology, population density and specialisation. Apparently diverse and unrelated features, consistent across time and place, confirms that cosmology is part of archetypal expression in all media, not ‘degraded science’ as De Santillana (1969) and others tried to demonstrate by ironically invoking ‘devolution’ into the diffusionist paradigm. Popular anthropology is particularly fond of correspondences, diffusion and devolution based on various assumed golden eras. As members of polities, scientists have some individual and collective vested interests in maintaining illusions of ‘cultural differences’. But scientists are equally compelled to study our species as objectively as possible.

The often silent assumption that media illustrate one another, such as art ‘illustrating’ ethnography or ritual; or myth ‘collating collective memories of major or repetitive events’; or symbols or divination features ‘deriving from’ analogies; should take caution that studies of cultural content and ‘origins’ agree with conscious, rationalised views of crafters and users. There was no conscious model, nor paradigm, for mathematical order in culture, such as the sizes of civic populations (Zipf 1949), or consistent average frequencies of specific features. Perception, expression and possibly meaning itself, is now revealed as ‘wired’ to archetype; and hidden by conscious habits, and our inability to recognise quirky rules as consistent. The core content of culture was static, and is likely to remain so, despite conscious discovery and diffusion of its features. Our repertoire of innate behaviour indicates that archetype guides nature and culture at several levels of scale, across media ‘boundaries’.

The archetypal structuralist model also finds support in some natural structures, such as the periodic table (Furter 2016). The high level of detail demonstrated in compulsive cultural expressions, invite automation of subconscious individual and social behaviour. Stalemates between rival anthropology models (Endicott et al 2005; Turner 2009) could be resolved by study of archetypal behaviour.

We could not know archetypes’ origin, as Plato realised, but we could study her expressions to explore our individual and collective roles in integration and self-actualisation. Our cultural works serve more purposes than we consciously know. Their study requires scientific integration and maturity. Structuralist anthropology has some experience in ‘tacking’ between data sets apparently in ‘disunity’, across time, place and layers of consciousness, as advocated by Alyson Wylie (1989, after Bernstein). Human sciences could extend its scope to global, diachronic behaviour. An opportunity, and perhaps a pressing need in the humanities, is to recognise differences between core culture and localised ‘branding’, and to inform society undergoing unprecedented globalisation and ‘culture’ shock. As nations and cities faction and fraction due to rival socio-economic bonds, the humanities could raise knowledge or our collective subconscious impulses, and our need for minor polity differences. A small step from modelling cultures, to modelling culture, may offer a leap in human sciences applications, validity and relevance, and potentially in general understanding of our place within nature.

References

Boole, G, 1854 /2003. Laws of thought. Buffalo: Prometheus Books

De Santillana G. and Von Deschend, H. 1969. Hamlet’s Mill: An essay on myth and the frame of time. Boston: Gambit

Endicott, K. M. and Welsch, R.L. 2005. Taking sides. Third edition. Iowa: McGraw-Hill/Dushkin

Furter, E. 2014. Mindprint, the subconscious art code. USA: Lulu.com

Furter, E. 2015a. Gobekli Tepe, between rock art and art. Expression 8. Italy: Atelier Etno

Furter, E. 2015b. Rock art expresses cultural structure. Expression 9. Italy: Atelier Etno

Furter, E. 2016a. Stoneprint, the human code in art, buildings and cities. Johannesburg: Four Equators Media

Furter, E. 2017a. Recurrent characters in rock art reveal objective meaning. Expression 16, June. Italy: Atelier Etno Expression 16, June. Also in Expression 2019; Message behind the image. Book 25

Furter, E. 2017b. Stoneprint tour of Paris. Stoneprint Journal 3. USA: Lulu.com

Furter, E. 2018a. ‘Babylonian Plough List decans. http://www.edmondfurter.wordpress.com

Furter, E. 2018b. Stoneprint tour of London. Stoneprint Journal 4. USA: Lulu.com

Furter, E. 2018c. Culture code in seals and ring stamps. Stoneprint Journal 5. USA, Lulu.com

Goldwasser, O. 2006. Canaanites reading hieroglyphs. Egypt and Levant 16: 121-160

Gunderson, L. H. and Holling, C. S. 2009. Panarchy; understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Washington: Island Press

Harrod, J. B. 2018. A post-structuralist revised Weil–Lévi-Strauss transformation formula for conceptual value-fields. Sign Systems Studies, November. USA: Center for Research on the Origins of Art and Religion

Hays, H. R. 1958. From ape to angel. London: Methuen

Jung, C. G. and Jaffe, A. 1965. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. New York: Random House, p392-393

Kuhn, T. 1966. Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 3rd ed. Chicago: Univ of Chicago Press

Levi-Strauss, C. 1973. From honey to ashes. Harper & Row

Levi-Strauss, C. 1955. Mathematics of Man. Paris: Bulletin International des Sciences Sociales 6:4.

Lewis-Williams, D., Pearce, D. 2012. Framed idiosyncrasy, method and evidence in the interpretation of San rock art. Johannesburg: SA Archaeological Bulletin 67, 75-87

Liritzis I. and Vassiliou H. 2003. Archaeo-astronomical orientation of seven significant ancient Hellenic temples. Athens: Archaeo-astronomy: the Journal of Astronomy in Culture, 17, 2003, 94-100

Looijenga, J. H. 1997. Runes around the North Sea and on the continent AD 150-700; texts and contexts. Netherlands: Rijksuniversiteit van Groningen, doctorate

Neugebauer, O. and Parker, R. 1969. Egyptian astronomical texts 3; Decans, planets, constellations and zodiacs. USA: Brown University Press

Paget, R. F. 1967. In the footsteps of Orpheus. London: Robert Hale

Parry, E. 2012. Rock art of the Matopo hills. Bulawayo: Amabooks

Pinzon, S. 1995. Early history of Belize. Ambergriscaye.com/earlyhistory/glyphs. Belize: Casado.net

Ranieri, M. 2014. Digging the archives; orientation of Greek temples and their diagonals. Athens: Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol 14, No3, 15-27

Sakellarakis, Y. and Sapouna-Sakellaraki, E. (1997) Archanes: Minoan Crete in a new light. Athens: Ammos

Temple, R. 2003. Netherworld. London: Century

Turner, T. S. 2009. Crisis of Late Structuralism. Perspectivism and Animism: Rethinking Culture, Nature, Spirit, and Bodiliness. Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America: Vol. 7: Issuse 1, Article 1

Wood, P. 2015. Ferguson and the decline in Anthropology. USA: National Association of Scholars, Jan 20

Wylie, A. 1989. Archaeological cables and tacking: the implications of practice for Bernstein’s options, beyond objectivism and relativism. USA: Philosophy of Social Sciences 19(1), March, 1-18

Zipf, G.K. 1949. Human Behavior and the Principle of Least Effort. USA: Addison-Wesley